Kashmir’s human rights crusader was arrested on trumped-up charges. Where is he?

The Modi government cannot stand criticism, so it silences its critics

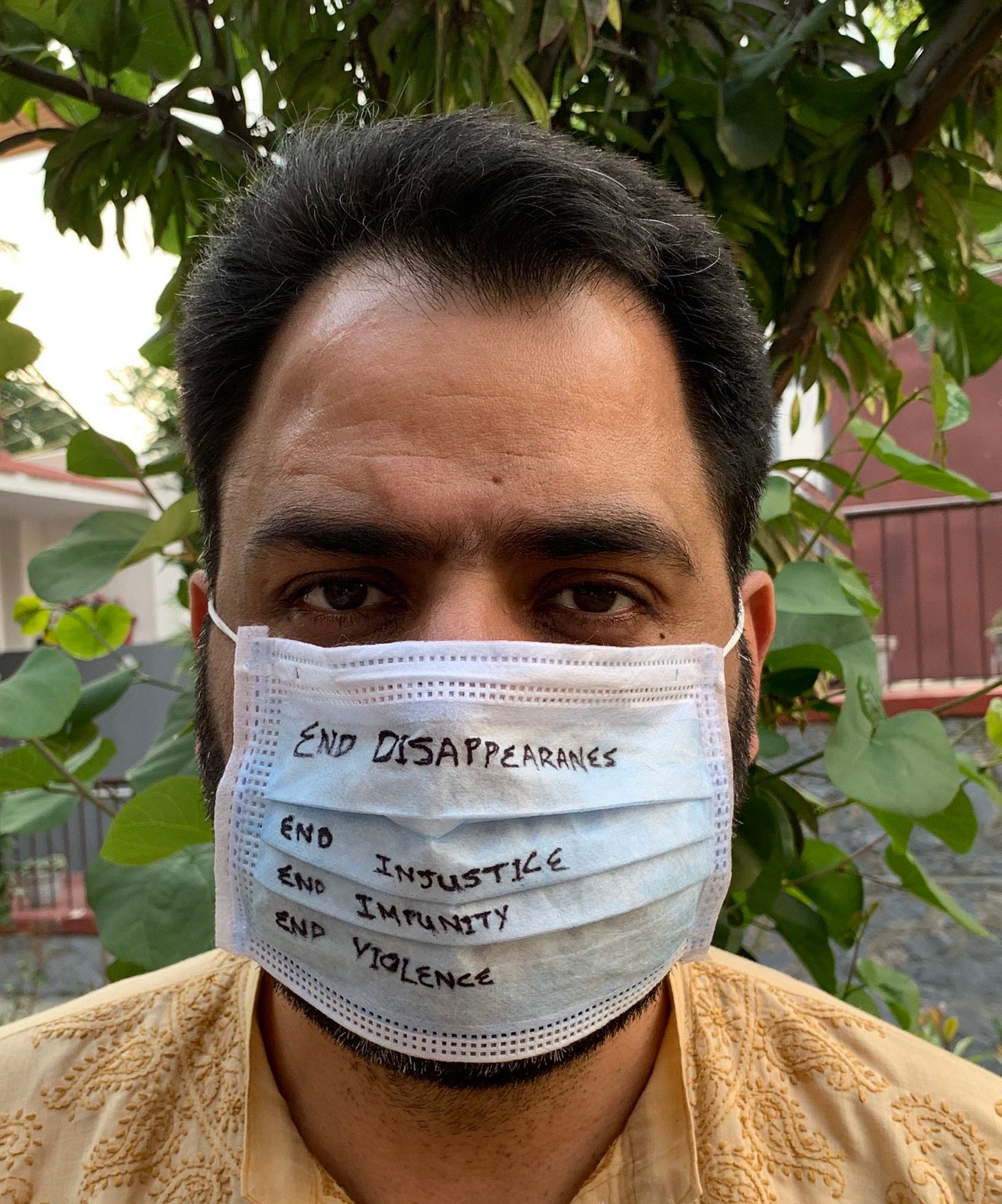

A bulwark against the atrocities of the Indian state in Kashmir, Khurram Parvez is the conscience-keeper of a country where ‘human rights’ is no longer a phrase you can use in polite company. He has few equals in his commitment to human rights in Kashmir, and now he has been jailed by the Indian state on charges of terrorism and sedition. His arrest in November should have sent warning bells to the rest of the world: Parvez is the recipient of prestigious human rights awards and a widely cited source on the Indian government's cruelty in the contested region. His arrest and internment is a transparent attempt to supress the story he told so well: of the atrocities in Kashmir, of the persecution of the only Muslim-majority state in India, and of the silencing of dissent. Kashmiri reporter Aakash Hassan has his story.

—Rana

Khurram Parvez was a teenager in the 1990s when Kashmir first descended into chaos. The armed rebellion against Indian rule and the brutal counterinsurgency spilled blood across a region renowned for its natural beauty: its snow-capped Himalayan mountains, its scenic lakes, and its lush meadows.

Every neighbourhood in Kashmir was affected by the violence; Parvez witnessed it especially closely. He was 13 years old in 1990, when Indian armed forces fired on a protest demonstration in Gawkadal, a locality in the downtown Srinagar, the main city of the region. More than 50 civilians were killed, including Parvez’s grandfather.

Parvez did not run. In 1996, as a student at University of Kashmir, he started a helpline—a kind of self-help group for fellow students affected by conflict.

Since the birth of the helpline, he has campaigned for human rights in the region. He has documented the cruelty of government forces, even exposing mass graves, and today he is one of the most prominent activists in Kashmir, where he co-founded and currently serves as Programme Coordinator of Jammu Kashmir Coalition of Civil Society (JKCCS).

In November 2021, the 44-year-old Parvez was arrested after officers of India’s National Investigation Agency (NIA), which investigates terrorism cases, raided his home and the office of JKCC. He has been accused of “terror-funding” and slapped with sanctions under the draconian Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA). Watchdog groups have warned that the law is being used as a tool to silence critical voices, like activists and journalists, by the right-wing Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) government led by Prime Minister Narendra Modi.

Thanks for reading Rana Ayyub’s fearless, change-making journalism. She needs your help holding power to account. Please consider a paid subscription—and you’ll never miss a post.

“We were still in bed when they (NIA) came and started searching the house early in the morning,” Sameena Mir, Parvez’s wife, told me. “They searched every part of the house, got hold of our phones and laptops, and left after five hours of intense searching, not without seizing some books, electronic gadgets (like phones) and taking Khurram along.”

It was later in the evening, the family said, that they were informed about his arrest. Parvez has been sent to Tihar jail in New-Delhi after 12 days of NIA custody.

Civil libertarians across the world expressed concern over Parvez’s arrest and sought his immediate release. Mary Lawlor, the U.N. special rapporteur on human rights defenders, said she was disturbed by the reports of the arrest.

“He’s not a terrorist, he is a Human Rights Defender,” she wrote on Twitter.

The Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) also raised concern over his arrest and criticised India’s anti-terror law, demanding an amendment to bring it in line with the UN’s standards for international human rights law.

India’s foreign ministry replied that the OHCHR “makes baseless and unfounded allegations against law enforcement authorities and security forces of India.”

Kashmir is disputed territory between India and Pakistan, with both claiming the region in its entirety but controlling it in parts. It remains the world's most heavily militarised zone, with hundreds of thousands of troops in the Indian-administered areas alone.

A vital career

JKCCS has released scathing reports on the human rights violations, including torture and forced disappearances, committed by Indian armed forces. Its most important work to date, though, has been its discovery and exposure of hundreds of mass graves where civilians and militants were buried by their killers in the Indian armed forces.

Working in a conflict zone can be fatal, and Parvez had several close shaves. In April 2004, while working as part of a monitoring team for Indian parliamentary elections in the region, the SUV carrying Parvez was torn apart by a landmine. Two of his colleagues, including journalist Aasiya Jeelani, a close friend, were killed. Parvez suffered injuries that cost him his right leg.

This devastating incident did not keep Parvez from his work. Instead, he began working with the International Campaign to Ban Landmines (ICBL). In 2007, rebel groups operating in Kashmir stopped using landmines following negotiations by Parvez, as part of ICBL, that led to rebel groups signing the Mine Ban Treaty and agreeing to a code of conduct in keeping with the Geneva Conventions.

Parvez and his colleagues at JKCCS have traveled the length and breadth of the region documenting violence, meeting its victims, and aiding them in their legal battles with Indian military and bureaucratic authorities. Parvez contributed to JKCCS’s mass grave reports, to the legal account of a rape case in which Indian armed personnel were accused, to reports about civilians killed in stage gunfights, to documention of the lives of ‘half widows’—wives of the disappeared—and to a report on mass killings. They have raised awareness at the UN about rights abuses perpetrated by Indian forces in the region, and they persistently advocate for peace and end to impunity.

Parvez has been invited as an expert on human rights to several visiting international embassies and UN delegations; JKCCS’s documentation is widely considered the authoritative account of violence in the region.

Restriction and suppression

In Kashmir in 2016, more than 100 protesters were killed and thousands more injured during an uprising following the charismatic rebel commander Burhan Wani’s death at the hands of the Indian army. Two months into the uprising, authorities stopped Parvez from boarding a flight to Geneva, where he was scheduled to attend a meeting of the UN Human Rights Council. He was arrested and released 76 days later, on the orders of a judge who called his arrest illegal and arbitrary. The following year, the Norway-based Rafto Foundation for Human Rights hailed the JKCCS for documenting “human rights violations in Kashmir under very difficult circumstances.”

In the summer of 2019, the Modi government unilaterally revoked Kashmir’s partial autonomy, dividing the conflict-t0rn state into two federally administered territories, Jammu and Kashmir in the West, bordering Pakistan, and Ladakh in the East, bordering China.

Over protests, the Modi government poured thousands more troops into the region. As the decision was announced in the Indian parliament, over 10 million people watched as their communications with the outside world were cut off. Hundreds of journalists had to rely on a few computers at the government-established media centre; it was the largest internet shutdown in a democracy in the history of the world.

Parvez and his colleagues at the JKCCS continued to document human rights violations meticulously, despite unprecedented restrictions. In August 2020, the JKCCS released a scathing report on how the digital siege had upended the lives of people in the region—including, in just the first five months, the loss to the local economy of 178 billion rupees 500,000 jobs.

“For a lot of people, Khurram Parvez and the organisation he worked for provided a space for victims to seek justice when authorities failed,” said a Kashmiri journalist who requested anonymity. “In many cases, even if victims or their relatives did not expect justice from authorities, he was someone who would listen to the grievances and record them. Unfortunately, with him in jail, hardly any ears left to hear such pleas or even record any abuse or excesses.”

Old records, new dangers

In October 2020, the NIA raided Parvez’s home, his office and other facilities where JKCCS members worked.

Parvez Imroz, a human rights defender and one of Parvez’s colleagues, is now the only member of the group visiting the office, located in a rundown building on the Bund along the river Jehlum. After the raids and arrest of Khurram, Imroz says there is fear among the volunteers who want to work at the JKCCS. These volunteers would document the daily violence and offer aid to victims; now the victims themselves are afraid, too.

“[The victims are saying:] ‘If this can happen Khurram, despite being internationally known–what can happen with us,’” Imroz says.

The charges against Khurram are false, Imroz tells me. “How can Khurram be related to terrorist activities while he was working againt the violence?” Imroz asked as he sat alone in his office. On the wall, a poster reads “Stop Crimes Against Humanity.”

“We have three aims–truth, Justice and peace–and we have been working towards it for the last three decades,” Imroz said. Imroz says that raids and Parvez’s arrest will not silence him, but he is concerned that the authorities now have documents with personal details, including names, of “lots of” victims—some acquired in the 2020 raid, and still more during Parvez’s recent arrest.

In November 2020, another activist in the region and Parvez’s colleague, Parveena Ahanger, a Nobel Prize nominee and winner of 2017 Rafto Prize, whose own son was disappeared, wrote to the United Nations to voice her fears about the seizure of the confidential and sensitive information relating to victims of human rights violations. It could, she said, be used to harass, intimidate, coerce, or induce the victims she has been working for.

“There is a grave apprehension” that the information may be “accessed by other agencies,” and can “lead to adverse consequences and reprisal against victims and families who have testified and are pursuing justice,” Ahanger wrote.

For Parvez’s wife, Mir, the last one month has been difficult, especially as she tried to answer questions from the couple’s son and daughter, who are 11 and 3 years old, respectively.

All the charges against Parvez are “frivolous,” she says.

“I know him as a person who would always speak the truth—who would always stand for the rights of his family, neighbours and the larger society,” said Mir.

Every kashmir story just obliterates the kiling and exodus of kashmiri pandits...all stories told by the champions of human rights starts conveniently after this time period of driving away pandits.... kashmir is the only muslim majority state of India.. from where Hindu pandits had to run away..any ways.. no solution in sight..