Danish Siddiqui: The Lens with a Conscience

Remembering my friend, the Reuters photographer, who tackled the world one click at a time.

I have spent most of yesterday excavating through memories with Danish Siddiqui; in my mind, in the minds of others that knew and loved him and in my digital archives. My Facebook has an album from 2009 with a dozen pictures from a vacation to Dharamshala. A comment under my photograph said, “Can I see some images of the place please? Right now I can only see you.” That was Danish Siddiqui; my dear friend, favorite critic, always mocking, teasing, and never letting me pose in peace.

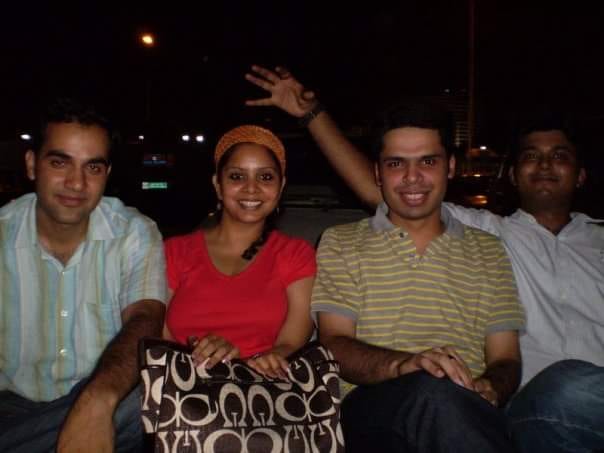

Danish, Poulomi Saha, Karen, Shuja ul haq, Mohsin Mughal and I, we were an inseparable group of twenty something journalists at NewsX. We were assigned to shoot and document projects under the guidance of our editor, Rajesh Sundaram, and some globally established professionals. One story took us to Baghpat in Uttar Pradesh. We were to report the illegal yet widespread caste-based practice of manual scavenging (manually cleaning, carrying, disposing of, or otherwise handling, human excreta in an insanitary latrine or in an open drain or sewer or in a septic tank or a pit), and Danish decided to do the camera work. He had no formal training other than a graduate degree from the Mass Communication Research Centre. The videos he took, the images he shot, drew loud cheers from the office that evening. That was his true love. Photography was his first language, and he was fluent and poetic in it.

Danish was not a man of words; he hated writing scripts and would often bounce them to his teammates, especially his closest friend, Poulomi Saha. He always found a way to tag along with the camera team. Danish would show us around Delhi, and while we ate at the Al-baik, he would chat up the cook, the waiter, or a random tourist. Everyone was a friend to Danish.

The nine months we spent together were one of the most memorable periods of my life. The six of us were inseparable, shooting, writing, reporting, learning, documenting, traversing the country looking for a story. On weekends we were mostly in each other's faces. Danish would almost always be the first person to message us in the group, “Shaam ko kya kar rahe hain?” (What are we doing in the evening?). We soon headed in different directions. Danish joined Headlines Today and another news publication in Delhi.

When work brought him to Mumbai, he would sit for hours at Mohammed Ali Road and Bandstand and stare into the endless magnitude of the city, clicking away with his camera. He loved shooting people. His photographs reflected his empathetic and responsible gaze. From the autowala to the Imam of the Mosque to a street hawker; his images had nuance, an inexplicable rawness and most important a respect for the autonomy of his subjects.

He noticed every wrinkle, every twinkle, a deep sadness or a momentary delight. Emotions that missed the eye were captured by Danish’s camera. One weekend, Danish took me to a small eatery in Mahim, very close to the iconic Makhdoom Shah Dargah, in Mumbai. “I want to show you something!” he said with childlike excitement. He opened his laptop to images of Mumbai that filled me with wonder. I had lived in Mumbai all my life and prided myself to know many of its obscure secrets. But the city Danish captured revealed a whole new facet of my home. There were photographs of public protests at Azad Maidan, a rally at Shivaji Park, men doing laundry at Dhobi Talao, a casualty ward at Sion Municipal Hospital. Much like him, his Mumbai had empathy and kindness, a naked compassion.

Within months of his arrival in Mumbai, Danish knew almost every human rights activist who lived in the city. He would often ask for insights on Dalit children jailed and oppressed under draconian laws, or the under trials from the minority community falsely accused in terror cases in rural Maharashtra. We lost touch soon after in 2016 as he traveled the world, turning out to be an asset for Reuters, but his gaze remained firmly rooted on the less privileged—the minorities, the laborers, the working classes, the transgender persons, the minors.

In the years I have known Danish, I never heard a change in pitch. He was gentle and courteous to the point of a flaw. When he was not covering assignments for Reuters, he would head out with his camera to capture images of stories long forgotten by the mainstream media, like the victims of the Muzaffarnagar riots of 2013. He stayed in touch with Poulomi till his final day, “In the last decade, the only time Danish admitted to being overwhelmed was when he shot during the second wave of the pandemic. That took a huge toll on him. He was completely broken,” she tells me.

In the past five years, when the frequency of our communication reduced drastically, I only knew Danish through his images. He was the journalist telling the world the most urgent stories through searing photographs. Such was the impact of his lens, every time there was an event in India, newsrooms would wait for a Danish Siddiqui image. From the Citizenship Amendment Act Protests to the Farmers Protests, the anti-Muslim carnage in New Delhi in 2020 to the devastating Covid wave in India, his lens never ceased to capture and apprehend.

He caught the prominent image of the Hindu Nationalist terror accused of wielding a gun at students of the Jamia University in New Delhi, during the citizenship protests, as cops stood in the background like mute spectators. Shaheen Abdulla, a student of Jamia who idolized Danish, wrote yesterday, “Danish kept coming back to his alma mater Jamia. He did not walk in a group. On the 30th of January 2020 when an armed terrorist turned his gun at the protesting students, I saw him push the shutter when the gun was pointed at him. I don’t know where he found the courage inside of him to do that.” It was an image that defined the lawlessness in India. The last two years of his work from India was a seminal document that will be preserved in the reams of history.

Images do things. They move people, collective consciousness, and even political forces. They not only portray and frame the world but also shape the understanding of it. The power of images in this era entrenched in the act of scrolling through visuals is unprecedented. Danish’s images were the ones that paused our incessant scrolling. They shook our idea of reality, as if confronting our own culpability in the devastation.

In January 2020, when India’s mainstream media was busy covering Donald Trump’s dinner with Narendra Modi in the national capital of Delhi, Danish shot the carnage happening in the backyard of the feast. He witnessed the mob lynching of a Muslim man, mercilessly beaten and made to chant the national anthem.

He held a mirror so powerful that it was impossible to avert one’s eyes.

He captured all scales and facets of tragedy during the first wave of the pandemic in India. The migrant laborers walking barefoot from cities to their homes in rural India, flooded hospital wards, exhausted medical professionals, neglected frontline workers, ignored and discarded crematorium workers, all juxtaposed against the celebratory election rallies and religious gatherings in the country led by Prime Minister Modi.

While Indian media posted selfies with the oppressors, it was Danish whose lens was fixed on the oppressed.

Danish and his camera were the relentless moral and ethical compass of Indian journalism and Indians alike. As his death has the world outraged and grieving, including a statement by the US State Department mourning his departure, the Indian Prime Minister’s silence is conspicuous, but not surprising. As social media trolls from the regime’s cohort celebrate Danish’s death, Narendra Modi and his cabinet ministers are yet to send out a condolence message. I am glad Danish had the privilege of being a journalist with Reuters and his international acclaim since his Pulitzer. There are many sharp and talented journalists that aren’t given due recognition despite their persistence in the face of brutal intimidation: Siddique Kappan has been jailed for nine months for covering the gang rape of a Dalit girl in Hathras, Uttar Pradesh. He was not allowed to perform the last rites of his mother who died waiting to see him one last time.

Journalists are often feted for our bravado and courage. The term has often been used for my journalism as well. But I can say with great conviction that my work was not a patch compared to that of Danish Siddiqui and his brave photojournalist cohort: Altaf Qadri, Tashi Tobgyal, Adnan Abidi or Arun Sharma. Three days ago, Danish communicated to his colleagues at Reuters that he had sustained a shrapnel wound. Another journalist who met Danish in Afghanistan last week said she was stunned that Danish decided to travel with the Afghan army to Spin Boldak, a region the Taliban was expected to seize. To be embedded with the Afghan army even for a day was taking a sure step toward death. Danish continued to be embedded with the Afghan army for more than seven days. But that was Danish. Committed to the truth, bearing witness, armed with his lens, ready to tackle the world one click at a time.

I had barely spoken to Danish in five years, but he spoke to me with every image he took. Infused with his courage, emotions and authenticity, each image to me conveyed his state of mind. I would look at his images and imagine the conversation he would have with his children, Sarah and Yunus, at the end of the day, translating the atrocities of this world for their young minds. I would hear second-hand anecdotes of his travel stories from Poulomi, and they filled me with pride, and some regret for a friendship that had fizzled out due to our daunting work lives.

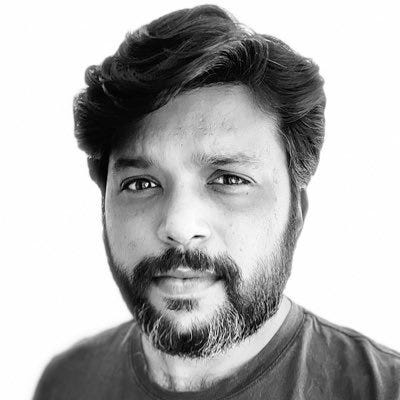

I had once requested Danish to click a profile photo for me and true to his nature he had responded with an enigmatic smile, “When it is time, I will.” You could not keep your promise, Dan. Rest in power, my friend.

Goosebumps! Lost a Powerful human!

May the tribe of such indomitable souls prosper and pave the way for the acts of courage that each person of the journalistic world has to perform in the differing roles to bring about justice in our society and effect the much required social reforms through a healthy democracy!!!